Pacific Reckoning: How Australia brought the first Japanese War Criminals to Trial at Morotai

- david's Blog

- Log in to post comments

Paper given at the Fighting to the finish: Australia in 1945 - Strategy, Victory and Legacy Conference, Melbourne 11 October 2025 Military History and Heritage Victoria based on a topic from my historical novel, Ashes and Sakura

Abstract

Between November 1945 and February 1946, on the island of Morotai, Australia convened some of the first war crimes trials in the Pacific. These tribunals prosecuted Japanese officers and soldiers accused of atrocities against Australian prisoners of war, confronting unique legal and logistical challenges. This paper examines the trial of Captain Tokio Iwasa, accused of murdering a captured Australian airman, as both legal proceedings and an expression of political policy.

Introduction

Morotai is a small island in the Halmahera group of the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia). Lying just above the equator between Western Papua and the Philippines, it is cloaked in dense rainforest and mountains. Between November 1945 and February 1946 Australia convened on this island some of the first war crimes trials in the Pacific.

Though little known today, Morotai proved pivotal in the war. The Japanese seized it in 1942 to build an air base, but swamp and jungle forced them to abandon the project leaving behind only a small garrison.

MacArthur saw Morotai’s value as a springboard for the Philippines. On 9 September 1944, the US 31st Division landed and secured the island within a day—suffering only a single casualty, from a falling tree. The surviving Japanese garrison melted into the jungle, many to die from starvation and disease. Within weeks, two crushed coral airstrips and naval facilities were in place. After Manila fell in March 1945, MacArthur shifted his HQ there, and handed Morotai over to the Australian Advanced Land Headquarters for the Borneo campaigns between May and July 1945.

On 9 September 1945, General Blamey accepted the surrender of the Japanese Second Imperial Army on Morotai. The island again served as a staging post, now for thousands of men from the Australian 7th and 9th Divisions impatiently awaiting repatriation after the Borneo campaigns. Shipping for the final leg home was unavailable: US vessels were tied up with Japan’s occupation, while Australia’s few troop and hospital ships were bringing home emaciated survivors liberated from Japanese prison camps in Singapore and elsewhere.

The remnants of Japanese hold-outs on the island surrendered in dribs and drabs in response to leaflets dropped in the jungle declaring the war over, filling the PW camp on the base.

In October 1945, the 34th Australian Infantry Brigade was formed on Morotai as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF). Volunteers from Borneo, Wewak, Bougainville, and New Britain were assembled on the island by November.

Yet the brigade’s move to Japan stalled. The Americans resisted sharing authority, and only after months of wrangling—a compromise hammered out with Australia pressing for a Commonwealth role—was the Morotai Force finally cleared to embark for Japan.

In the meantime, the Morotai Force administered the island and exercised military control over nearby territories until Dutch colonial rule could be restored. Alongside the surrendered Japanese PWs, the Force also guarded those accused of war crimes brought in from the surrounding islands. Investigators were racing against the clock, gathering evidence and arresting war crime suspects.

Rumours of atrocities and the Webb reports

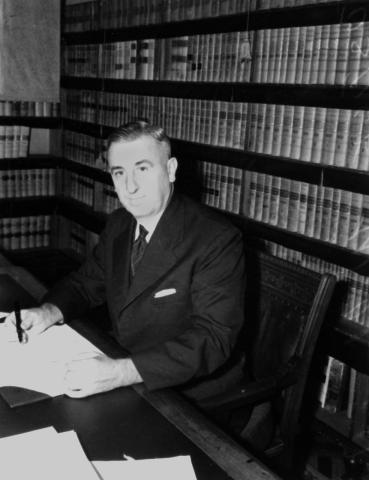

In 1940 he became senior puisine judge and chief justice. He was knighted in 1942. From 29 April 1946 Webb presided over the sittings in Tokyo of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East where 28 major war criminals were indicted.

[State Library of Queensland 127840]

After Japan’s surrender, Australia moved quickly to assert its sovereignty by conducting its own war crimes trials against Japanese suspects.

Preparations had begun much earlier. In June 1943, alarmed by reports emanating from the field of atrocities in New Guinea, the government appointed Sir William Webb to investigate. His inquiry soon revealed violations on a horrific scale. The findings were kept secret until war’s end—partly to shield victims’ families, partly to avoid Japanese reprisals against Allied prisoners.

As the Allies advanced through the Southwest Pacific, many more atrocities surfaced. MacArthur and Blamey authorised Webb to visit crime scenes and interrogate suspects and witnesses. Two further reports were presented to parliament. Though the Webb reports could not serve directly as evidence in war crimes trials, they guided investigators after the war—pointing to suspects, witnesses, and locations to pursue.

The Allies established a three-tier system for prosecuting Axis war crimes. Class A covered senior political and military leaders accused of beginning and waging aggressive war, to be tried in international tribunals at Nuremberg and Tokyo. Class B addressed conventional war crimes against combatants; Class C dealt with crimes against humanity pertaining to civilians. Trials in the latter two categories were conducted by individual Allied powers under their own military courts.

At first it was intended that Class B and C trials be held at the scene of the crimes by whichever Allied nation had the greatest number of victims. This proved impractical. Instead, Australia, Britain, the United States, and the Netherlands informally divided responsibility for the Pacific theatre, each nation prosecuting crimes in the zones it controlled or where it had overseen the Japanese surrender. Australia’s remit thus extended beyond its own territories to areas it occupied at war’s end.

Morotai became one of five venues for the first phase of Australian trials (1945–47), alongside Labuan in British Borneo, Wewak, Rabaul, and Darwin. In the second phase (1947–51), trials were also held in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Manus Island.1

The novelty of exercising extra-territorial jurisdiction over persons not otherwise subject to Australian law was deemed to require fresh legislation. On 4 October 1945 a hastily drafted war crimes bill passed both houses of Parliament in a single day and received royal assent one week later.2 The War Crimes Act 1945 and its subsidiary regulations empowered the Commonwealth to try persons accused of war crimes committed anywhere—within or beyond Australia—against anyone who had at any time been resident in Australia, or against any British subject or citizen of an Allied Power. It also authorised the Courts to sit at any place, within or beyond Australia (ss. 7, 12).

Trial of Captain Tokio Iwasa

The first military court convened under the War Crimes Act opened on Morotai on 29 November 1945.

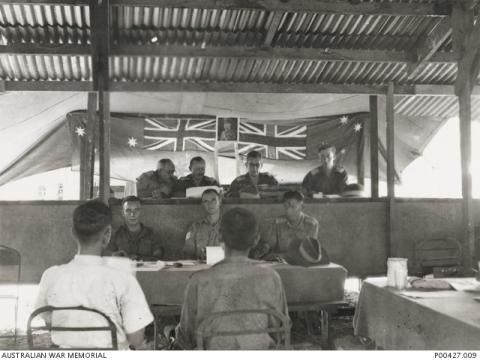

It was conducted in a simple hut with a corrugated iron roof beside the Japanese PW compound. Two Australian flags flanked a portrait of King George VI. The sitting of the Court was intentionally open to the public. A hundred servicemen on the island were chosen by ballot to witness the proceedings (reg. 14).

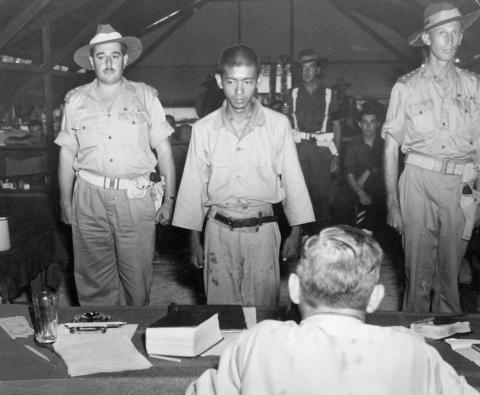

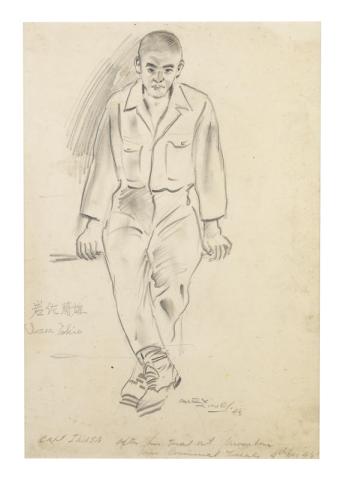

The accused was Tokio Iwasa, a junior officer of the 211 Regiment charged with murdering a prisoner of war, a captured Australian airman. The facts were not in dispute.

On 23 March 1945, at Major Tamura’s headquarters in Beo, on the Talaud Islands north of Morotai, four Allied airmen—three Australians and one American—were brought into a jungle clearing. They were tightly bound, though in fair health apart from the American, who wore a head bandage. Each had been captured after his plane went down in the preceding months.

That day marked the ceremonial presentation of regimental colours from the emperor, and a public execution was staged as the climax. At noon, four companies of Japanese soldiers assembled under their officers, each with a large wooden cross before it. The prisoners were blindfolded and fastened to the crosses.

One by one, the company commanders summoned untested privates to act as executioners. At the commands—Fix bayonets! Prepare to lunge! Lunge!—steel drove into the hearts of the condemned. The airmen made a muffled groan before their bodies sagged against the restraints. The bayonets were withdrawn, the victims cut down, and the bodies hastily buried.

The soldiers then marched off behind their regimental flags.

It was this trial, designated M9, that the military court fashioned the template for later trials on Morotai in at least five ways:

- Composition of the Court

The War Crimes Act established military courts modelled on general courts-martial in the British system. Australia’s class B and C trials thus remained primarily military affairs, in contrast to the international tribunals of civilian judges at Nuremberg and Tokyo—where Webb himself would serve as Court President.

Courts-martial in the British system are adversarial, with prosecution and defence, but unlike common law courts they have neither judge nor jury. Verdict and sentence are determined by a panel of officers, usually by majority vote. As these officers are not necessarily legally trained, a judge advocate is commonly appointed to advise on points of law.

In M9, the military court comprised two senior officers from Advanced HQ AMF and an RAAF squadron leader, as the victim was an airman (reg. 8). Of the three only the RAAF officer had formal legal training. A captain from Australian Army Legal Corps acted as judge advocate. The officers wore their campaign ribbons and medals; the defendant stood stripped of rank insignia.

Prosecution and defence were drawn from a pool of eleven lawyers of the Australian Army Legal Corps—the Defending Officer only being given a few days to prepare the case.

- Setting the ground rules.

The Morotai trials were hampered by limited legal library resources, oppressive heat and humidity—which kept the officers’ batmen busy with uniforms changed twice daily—and crushing workloads.

At the opening of M9, when Iwasa was asked to enter a plea, the Defending Officer interjected, questioning the constitutional validity of the War Crimes Act and the power of the Court to try the accused. A delay was also sought until Iwasa’s superior officers were tried first. Both requests were overruled. Once the Court in M9 established the ground rules governing its jurisdiction, and other issues raised by the Defending Officer, these were treated as givens in later trials and simply noted, expediting proceedings.

- Relaxed rules of evidence.

The War Crimes Act included a controversial relaxation of the rules of evidence. Under common law, hearsay is normally inadmissible, and any document tendered in evidence must undergo rigorous examination. The Act relaxed both rules, on the grounds that most war crimes would otherwise escape punishment (s. 9.1).

The Prosecution in M9 drew upon both forms of relaxed evidence—hearsay and documentary. Most damaging was Iwasa’s own signed statement, given during interrogation, acknowledging he had given the order to kill—though it was unlikely he understood that by signing, it could be used in evidence against him. Despite this, the court was satisfied that he had signed without duress and the exhibit was deemed authentic and admissable.

- Types of sentence

[AWM OG3667]

The prosecution case, comprising witness testimony and documentary exhibits, concluded in just over a day. The Court adjourned until the afternoon, when the accused was invited to adduce evidence in his defence. He declined. Final addresses were then delivered by prosecution and defence, followed by the judge advocate’s summation of the applicable law. After deliberating for twenty-five minutes, the Court returned a verdict of guilty.

Under the War Crimes Act 1945 (s. 7), the Court was empowered to impose the following penalties:

- death, by hanging or shooting;

- imprisonment;

- a fine; or

- restitution for stolen or destroyed property.

The latter two penalties were never applied in Australian trials, pursuant to Allied agreement that only grave offences would be prosecuted. A sentence of death required unanimity, or in cases where more than three members sat, a two-thirds majority (s. 11.3).

Upon reconvening two weeks later, the Court sentenced Captain Iwasa to death by shooting.

- Sentence subject to confirmation

Under the War Crimes Act, only the Governor-General or his delegate could confirm, mitigate, or commute the sentence of a military court (ss. 5, 6; regs. 18–19).

In practice, all guilty verdicts from the war crimes trials on Morotai were subject to confirmation by the Acting Commander-in-Chief, Lt-General Vernon Sturdee, in Melbourne, on the advice of the Judge Advocate General. This arrangement had the political expediency of distancing the Chifley Labor Government from direct responsibility for executions. The Labor Party, long opposed to capital punishment, had consistently in the past commuted death sentences in civil courts, and abolition was part of its platform.

Yet public sentiment after the war left little room for leniency. Extracts from Webb’s first report, released in September 1945, coincided with press stories of Australian prisoners returning from Singapore. Outrage among war widows, repatriated prisoners, RSL branches, and the wider public overrode Labor’s anti-capital punishment stance.

Under Chifley’s government, death sentences would be carried out in 132 of 137 confirmed cases.3

In M9, after Captain Tokio Iwasa was sentenced, the Defending Officer issued a petition against the verdict and severity of sentence to the confirming officer, Sturdee, on two grounds:

- that Iwasa acted under orders from senior officers, lacking free will and committing no atrocity on his own initiative;

- that Iwasa had never been instructed in the treatment of prisoners of war under international law.

The petition was supported by a statement from Major Toshio Tamura, Iwasa’s commanding officer, taking full responsibility for having given the original order.

On the Judge Advocate General’s advice, Sturdee dismissed Iwasa’s petition on 31 January 1946 and issued death warrants for him and the other condemned to be flown to Morotai.

Reactions to the death sentences

Reactions among servicemen and women to the death sentences at the Morotai war crimes trials were mixed.

A serviceman from Dubbo who witnessed proceedings on Morotai genuinely tried to understand the Japanese mentality behind the atrocities. He concluded that the average Japanese soldier was “half animal and half child”—a dangerous tool when under harsh control, ignorant of the rules of war, and obedient without question. Freed from domination, however, he was a carefree being content with little and inclined to peace. Responsibility, as far as he was concerned, lay with the officers who issued criminal orders, not the rank and file. (Dubbo Liberal and Macquarie Advocate, 5 January 1946, p. 2)

In the prison compound, moments of fraternisation coloured the final days. On the eve of the executions, the condemned wrote letters, played music, and sang songs. There was even laughter. Iwasa took up his bamboo flute, playing a lively tune while AWAS nurses from the base hospital danced the jitterbug. One prisoner sketched a cartoon of Iwasa before a firing squad of AWAS nurses armed with Owen guns, captioned in English: “Please don’t forget the shooting!” A senior officer, fearing public reaction at home, banned photostat copies (The (Melbourne) Herald, 3 August 1946, p. 11).

Others sought retribution. On Labuan, an RAAF squadron leader, medical officer, and adjutant asked to join the firing squad for a condemned prisoner sent to Morotai. There is no evidence their request was granted (The (Sydney) Sun, 11 December 1945, p.2).

Execution

Once the decision was taken to carry out the death sentences, the presence of part of Morotai Force on the island ensured that enough men were available to form firing squads. Yet there was an immediate difficulty: the Australian Army had no experience in such matters. In the past, Australian courts-martial had handed down death sentences for desertion and other offences, but all had been commuted to imprisonment. Guidance therefore had to be sought from the British whose Standing Orders on military executions were deemed the most humane, and on 25 February 1946 Army Headquarters in Melbourne sent elaborate instructions to Morotai Force.

The first firing squad in the history of the Australian Army took place at dawn on 6 March 1946 on a secluded beach lined with coconut palms, not far from the PW compound. Thirteen convicted war criminals were shot in four batches, with others to follow later in the month. Twenty seasoned soldiers were selected for the firing squads, each given the chance to decline on conscientious grounds. Because of the large number of executions, the standard detail of ten riflemen per prisoner was reduced to five. At first light the Provost Marshal assembled his men. Their rifles were loaded and racked; two were covertly charged with blanks so that no soldier would know for certain he had fired a fatal round, an ancient practice from the days of musketry, though with modern weapons the difference in recoil could likely be felt.

Newspaper reporters waited at the site, though forbidden to take photographs or describe the grisly particulars. At 7.30 a.m. the first group of condemned was brought out. As they were strapped into their chairs, they chatted, laughed, and sang. They refused the offer of black hoods, agreeing only at the Provost Marshal’s request so as to ease the conscience of the men in the firing squad. White discs were pinned to their chests as targets, and the firing squad—which had spent the preceding days practising—took position fifteen yards away. The prisoners shouted Banzai three times; at the final cry the order was given to fire—not as a shout, but just loud enough for the firing squad to hear. A medical officer stepped forward with his stethoscope to confirm death. A rumour exists that a coup de grâce had to be given to one of the condemned by the Provost Marshal.

After each execution a Japanese burial party approached, bowed reverently before the body, and carried it away.

The premature ending of the trials on Morotai

Between November 1945 and February 1946, 25 war crimes trials involving 148 defendants were conducted on Morotai.

By the end of March 1946, most of Morotai Force had redeployed to Japan, leaving too few men to maintain the prison compound, kitchens, administration, or officers’ mess. At the same time, the Dutch were pressing to reassert control of the island before Indonesian nationalists could take hold.

The trials were hurried to a close. The premature ending of the Morotai trials left the Court’s mandate unfulfilled, and many crimes in the region went unprosecuted.

Of the 30 Japanese war criminals sentenced to death in the Morotai and Labuan proceedings, only 16 were executed on the island (11 from Morotai, 5 from Labuan). The remaining 14 were transferred to Rabaul, where their death sentences were carried out later in 1946 or in 1947.

Bibliography

British Royal Warrant, Regulations for the Trial of War Criminals. A.O. 81/1945. In the Avalon Project, Nuremberg Trial Final Report Appendix E. Yale Law School. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/imtroyal.asp

Fitzpatrick, Georgina. Death Sentences, Japanese War Criminals and the Australian Military. In Georgina Fitzpatrick, Tim McCormack, and Narelle Morris, Australia’s War Crimes Trials 1945-51 (Brill, 2016), Ch 11, 326-370.

Fitzpatrick, Georgina. The Trials on Labuan. In Georgina Fitzpatrick, Tim McCormack, and Narelle Morris, Australia’s War Crimes Trials 1945-51 (Brill, 2016), Ch 14, 429-470.

Fitzpatrick, Georgina. The Trials on Morotai. In Georgina Fitzpatrick, Tim McCormack, and Narelle Morris, Australia’s War Crimes Trials 1945-51 (Brill, 2016), Ch 11, 373-407.

Gormley-O’Brien, David. Ashes and Sakura: an Australian story of the making of a Pacific nation (Nihil Alienum, 2025)

Lynch, John. Three Months on Morotai: the War Crimes Trials of Captain G.F.Lynch, Victorian Historical Journal, Vol. 25, No. 1, June 2024, 167-178.

Paes, Michael. The Australian Military Courts under the War Crimes Act 1945—Structure and Approach. In Georgina Fitzpatrick, Tim McCormack, and Narelle Morris, Australia’s War Crimes Trials 1945-51 (Brill, 2016), Ch 4, 103-133.

McCormack, Tim and Narrelle Morris, The Australian War Crimes Trials, 1945-51. In Georgina Fitzpatrick, Tim McCormack, and Narelle Morris, Australia’s War Crimes Trials 1945-51 (Brill, 2016), Ch 1, 5-26.

Military Tribunal of Iwasa, Tokio (Captain), NAA A471/80718.

Sissons, David. Papers of DCS Sissons, National Library of Australia MS 3092, Box 28: ‘Death Sentence’

Wakeling, Adam. Stern Justice. Melbourne, Vic: Viking, 2018.

War Crimes Act 1945 (Cth). In Georgina Fitzpatrick, Tim McCormack, and Narelle Morris, Australia’s War Crimes Trials 1945-51 (Brill, 2016), Appendix 1, 810-815.

Wood, James. The Forgotten Force: the Australian military contribution to the occupation of Japan, 1945-1952 (St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 1998)

Notes

1 The Ambon trials were transferred to Morotai on 18 Jan 1946 when the Dutch arrived to recover their colonial possessions.

2 The War Crimes Act 1945 followed very closely the British Royal Warrant enacted on 18 June 1945 with a series of regulations to convene military courts in the area of the former Third Reich to try alleged war criminals. In the M9 trial both the Defending Officer and Prosecutor would allude to ‘the very curious and quaint methods of drafting employed by the draftsman [of the Act]’.

3 The Menzies conservative coalition in war crimes trials later in 1951 on Manus Island had no such qualms and took upon itself and its cabinet to confirm the death penalty. The Menzies Government was only responsible for the final five convicted who were hanged in the one day on Manus Island in 1951.